Authors Note:

When I stumbled upon the story of Sidney E. Frank I couldn’t help thinking that one day someone will turn his life into a movie. However, even though essentially a guidebook for genius marketing, Sidney’s life is poorly documented and some references directly contradict themselves. So if one identifies inaccuracy, omissions, oversights or any other mistakes please contact me at ivannonveiller@gmail.com and I will make sure to stand corrected.

I always thought that making lots of money is one of the most satisfying accomplishments in man’s life. But not as satisfying as giving it away. When my good friend and editor of Arts and Opinion, Robert J. Lewis, heard about me writing this article, he send in an old quote that encapsulated this same idea, almost 400 years ago.

“Of great riches there is no real use, except it be in the distribution”

F. Bacon

Be the Only One

Sidney Frank was 76 years old when he walked into the O’Lunney’s Times Square Pub and ordered a glass of Vodka. It was a cold, October afternoon of 1995, and New York Yankees were loosing to Mariners.

However all the eyeballs were staring at CNBC.

Microsoft had just released the 1st version of Internet Explorer and Alan Greenspan was actively defending low interest rates and increasingly available capital.

The invention of World Wide Web, allowed anyone, for the first time in history, to access a completely untapped international market. Companies were about to experience whopping growth under the influence of venture capital and rapid succession of IPOs.

The dot-com bubble was forming.

But Sidney Frank wasn’t into technology. He saw something completely different. He realized that a new era of speculative exuberance was going to create a demand for luxury drinking and sophisticated cocktails. He anticipated that afternoon the ostentatious contemporary mixology scene

and was maybe the first person to realize that a product was missing from the shelves. A new category of Vodka, way above the current $20 range.

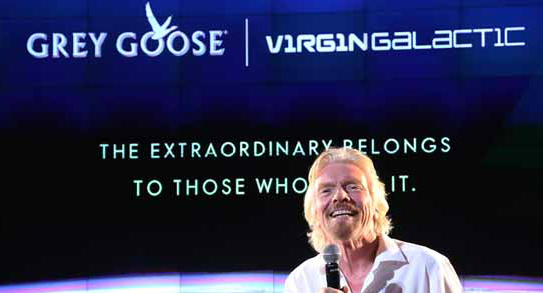

Less then eight years later, at the age of 85, Sidney Frank was single-handedly controlling over 85% of the superpremium world market share. Shortly thereafter he sold Gray Goose to Baccardi for $2.3 billion.

He gave most of it away within two years: to friends, artists and educational institutions, including a $120 million donation to Brown University and a $23.8 million bonus to his secretary shortly before his death in January 2006.

During those eight years, he used his insights into human behaviour as inspiration for what we now call experiential marketing. Some say he invented guerilla advertising, and, more than anyone, was able to inspire mass-market appeal for luxury consumption.

This is his story.

Alcohol As a Fuel

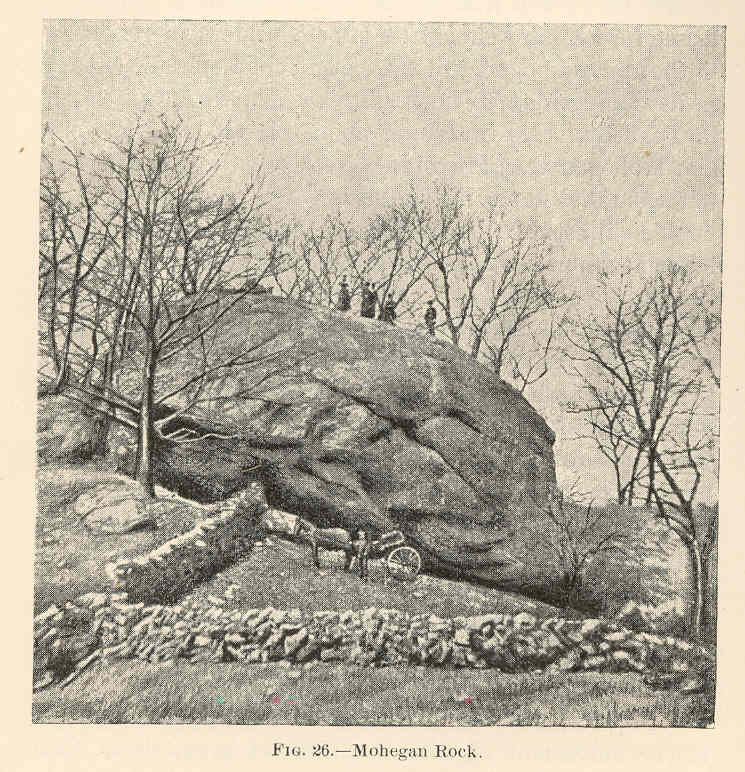

Frank recalled his childhood in 1920s as poor but happy. He was always up long before sunrise and helped his father grow corn, potatoes and onions. “We had horses to plow the field, and we had a hay field to feed the horses.” He grew up on a farm in Montville, Connecticut near a giant Mohegan Rock from top of which one could see Long Island. At the age of 12, as a first entrepreneurial venture, he built a ladder with his brother and charged people a dime-a-climb for the view.

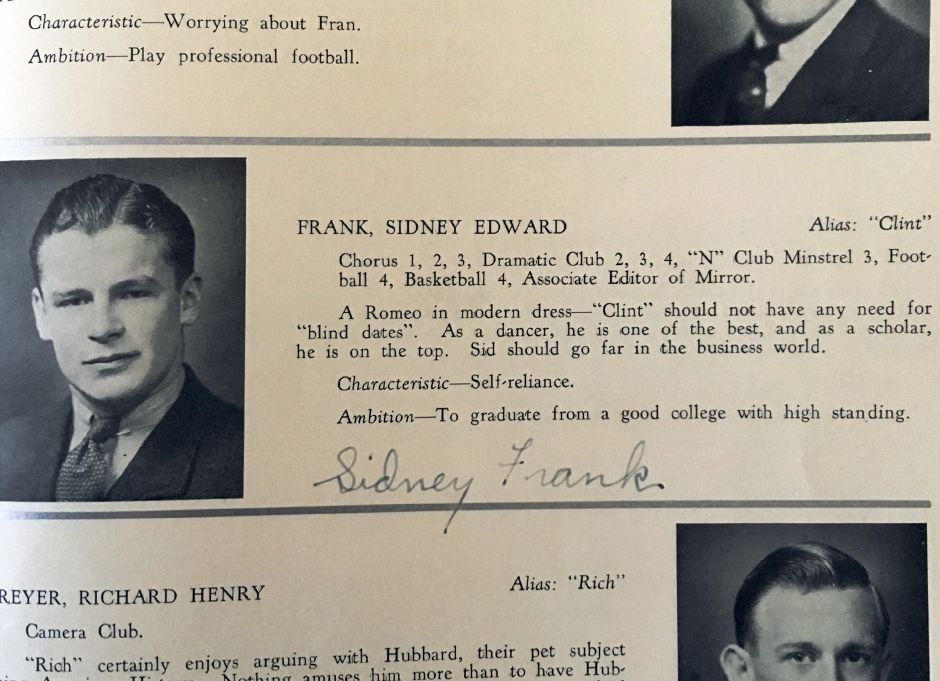

As a kid, he dreamed of making it to the big world, often gazing at the Manhattan skyline while traveling by train to visit his cousins in Brooklyn. By the summer of 1942, after years of hard work, he managed to save just enough money for a one-way bus ticket to Rhode Island and a year of tuition at Brown.

When he arrived at the university he slept for first time on real bedding, not flour and grain sacks that his mother sewed together for bedsheets.

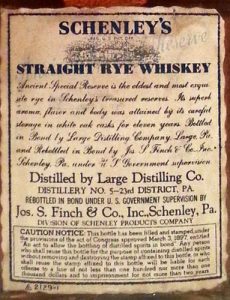

His roommate, another freshman, Edward Sarnoff, introduced him to the world of the wealthy including Louise Rosenstiel, daughter of Lewis Rosenstiel, founder of Schenley Industries, one of the nation’s largest distillers. Few years later they married.

Frank had to drop out of Brown after one year because he couldn’t afford tuition but managed to develop useful habits that he claims helped him succeed later in life.

His roommate, another freshman, Edward Sarnoff, introduced him to the world of the wealthy including Louise Rosenstiel, daughter of Lewis Rosenstiel, founder of Schenley Industries, one of the nation’s largest distillers. Few years later they married.

Frank had to drop out of Brown after one year because he couldn’t afford tuition but managed to develop useful habits that he claims helped him succeed later in life.

A newspaper ad for an position at Pratt & Whitney caught his attention, but he was only one of many in a long line of applicants. However the hiring manager, noting that Frank had just spent a year in Providence, said, “Oh, you went to Brown? I did, too. Go see the guy in engine testing. I think there’s an opening there.” Frank did. “Of course, you can use a slide rule?” asked the second man. Frank found a store that sold slide rules, read the directions and returned.

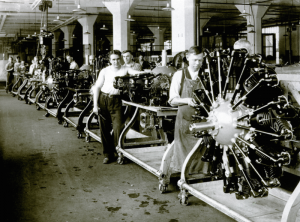

He was hired as a troubleshooter and learned to assemble and disassemble Pratt & Whitney aircraft engines. During World War II, he served as a manufacturer’s representative in India and China, exploring ways to improve engine performance and enabling aircraft to deal with high altitudes by implementing alcohol injection systems for aircraft engines.

Back in the United States, he eventually convinced Louise Rosenstiel to marry him. “She accepted my sixth marriage proposal.” One day, her father asked Frank: “What are you doing, son?” Frank said, “I work for Pratt & Whitney.” “Do you know anything about alcohol as motor fuel?” “We use it on takeoff in our R2800 engines. It gives us 20 percent more power.” So Rosensteil offered Frank a job at the Schenley division that distilled alcohol for motor fuel. And that’s how Sidney Frank entered the liquor business.

Scotch and Whisky

Frank achieved huge success at Schenley Industries. In summer 1948 he anticipated a glass strike so he rented every warehouse in the country which he filled with the raw materials for bottle production. When few months later a national strike hit all liquor companies, Schenley was the only distributor with glass.

In 1950 Schenley bought a Scotch plant in Scotland. The distiller called up requesting someone to come over and fire two VPs that were getting drunk every night. So Frank took a plane to Glasgow at a time where laws were restricting regulating the production of spirits in Scotland and found that the distillery causing problems was operating just two days a week, a practice based on outdated English liquor laws. He didn’t think that was much because Jack Daniel’s and Jim Beam were doing

up to 10 million back in US. So he increased distilling from 1 to 3,6 million bottles per year. At the time the cost was a $1 per gallon and they sold it in States for $5. Frank became a star and Schenley eventually became one of the largest liquor companies in the United States. One of the “Big Four” including Seagram, National Distillers and Hiram Walker. Frank eventually rose to the company presidency but butted heads with his father-in-law, and finally started his own company in 1972. Sidney Frank Importing Company. “It was just me, my brother, and a secretary.” But it was no overnight success. Frank was forced to sell off personal assets to keep the company running and started out by supplying Gekkeikan Sake to sushi restaurants.

Jägermeister: Gorilla and Guerrilla Marketing

One of the things Frank has learned was to not build a distillery until there was enough money to do it properly and enough production to put in it, so he began looking for anything that had a niche to import.

During the tough times, he would stroll around New York neighborhoods to see who was drinking what in the bars. During a late night ride he saw German immigrants downing an odd-tasting herb liqueur from the Fatherland.

It tasted like licorice, root beer and cough syrup. But it was an interesting product and there were a lot of Germans in the country. However in a moment of epiphany Frank saw another niche: the hard-partying college kids. Why or how he never explained it but he decided to take Jägermeister from elderly blue-collar German immigrants and transform it into a hot student brand.

He sent a telegram to the president of Jägermeister in Germany and asked if he would meet him.

And so they went for dinner. “I’d like to have Jägermeister for the States.” Frank said. “We already have commitments for most of the country, but we still have Maryland to Florida left.” President said, “I’ll take it.”

Next year however the owner of Jäger flew to Florida and asked his West Coast importer to take him to Disneyland. They got lost, so he figured his importer didn’t know the territory and that’s how Frank got the whole country in 1973.

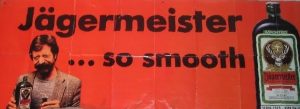

Frank had no money for advertising but when an article at The Baton Rouge newspaper said that Jägermeister is an instant Valium and theorized that it was an aphrodisiac Frank made a million copies of that it and single handedly drove all over Louisiana bars to show it.

When he reached Louisiana State University he assembled a team of hot girls, dubbed “Jägerettes”, and dispatched them to New Orleans bars to hand out photocopies of the story, flirt with male students and shoot Jäger into guys’ mouths with a spray gun.

Frank also put up eight massive Jägermeister billboards in the area. They were showing a drunk man and the words SO SMOOTH in capital bold Helvetica, playing on Jager’s sarcastic appeal.

All over the country, Jäger shots became the favorite symbol of buck-wild partying, and to this day the brand remains one of the hottest in the industry. At the time not a single alcohol expert could explain the Jäger phenomenon, they shrugged and called Sidney Frank a promotional genius.

“It’s a liqueur with an unpronounceable name,” said Ted Wright of Liquid Intelligence. “It’s drunk by older, blue-collar Germans as an after-dinner digestive aid. It’s a drink that on a good day is an acquired taste. If Sidney Frank can make that drink synonymous with ‘party’—which he has—he can pretty much do anything.”

No one realized at the time that Sidney Frank had single-handedly invented guerrilla marketing.

Vodka From France With an English Name?

Frank knew that vodka is the worlds nearest thing to an organic money machine. You can make vodka out of grain or potatoes, or any other organic material that will ferment to produce an alcoholic brew, which can be then concentrated through a simple distillation. If you add juniper berries or other so-called botanicals spices you get what the world knows as gin. If you leave it as is you can call it vodka. Vodka is quick and cheap to make. About 60% of what goes into the vodka bottle is water yet can be sold for eye-popping amounts. In the distilled-spirits business vodka dominates with 26.5 percent, while rum has 13 and gin 7.

Knowing this, Frank choose to create a vodka brand that would be almost twice as expensive – and twice as profitable – as anything else on the market including Absolut, the Swedish premium-blend that had taken the US by storm in the 1980s.

This was quite a challenge since rational and even the image-driven consumers don’t usually give away twice the amounts unless they can somehow be persuaded that it’s worth the money.

Frank’s stroke of genius was to distil his vodka in France. A country with a reputation for luxury products and superpremium prices. It’s all about brand differentiation. “France has the best of everything,” he liked to say. “It’s the home of luxury. We can bottle that.”

Frank loved the Cognac region and it’s chalky soil that gives life to some of the world’s most exquisite grapes. So he approached a local – François Thibault – son of a winegrower and Maître de Chai (Cellar Master).

Thibault graduated from the University of Bordeaux II with a degree in oenology (wine making) and was known for his work as the head of wine production department at Henri Mounier that specializes in Cognac and Pineau des Charentes.

François Thibault was taking something of a risk in 1997 when he quit his job and opened a distillery under the noses of the great Cognac producers. But he knew Frank was on to something. Vodka can be bottled and sold almost as soon as it’s made, where French law requires even the least expensive category of Cognac to be aged at least two years in expensive handmade French oak casks. This requires warehousing and inescapable losses since Cognac aging in the barrel evaporates at the rate of around 2% a year or the so-called “angels’ share”.

He sourced the best wheat France could produce. He was tipped off by a pastry chef in Paris about where to find it (French winter wheat from the Beauce region near Paris). He used naturally filtered spring water from the Massif Central and fine-tuned the distillation process until he got the result he wanted: irreproachable quality and vodka that had its own character.

Within a year Sunday Frank’s first batch of vodka was ready to be made.

He called it Grey Goose.

Today the company has a make-believe explanation for the distinctly un-French name. It was inspired, they say, by “the geese that have made Cognac their home and are celebrated in the region.” However Frank’s decision to call his vodka Grey Goose almost certainly predated his decision to produce it in the Cognac region.

He simply loved the sound and already owned world-wide rights to it, thanks to an earlier venture involving Liebfraumilch, a German wine of the same name. “These were German white wines that were briefly hip but faded into oblivion. I remember there was always something in the name that had magic with the consumer,” said Frank.

And so, as the first bottles of Grey Goose were being filled in France in the summer of 1997,

Frank was done with the development of a masterful event-based marketing strategy that was about to take over the US market by storm.

The Why and Cezanne

The cornerstone of Frank’s strategy was simple. To build a refined and tasteful brand of unrivaled quality: elegant, stylish and cosmopolitan.

The brand needed a great story. Or what Nietzsche called the “why.” The story had to be enticing, memorable and easily repeatable.

Goose’s story rested on following key points:

Origin. It comes from France, home of luxury products.

It is not another tasteless, rough, north-European vodka. It’s a chef-d’œuvre crafted by French masters.

Composition. It is distilled in a five-step process from winter wheat grain with unspoiled artesian spring water and is filtered through Champagne limestone which gives it its crystal clear appearance.

Taste. It has a smooth and floral aroma with a hint of citrus. A rounded texture and a distinct character that is a result of an extraordinary passion for spirit making and an unparalleled commitment to the highest possible quality.

As advertising was becoming digital, increasingly fragmented and had less impact on consumers, Frank was counting and his relationship with bartenders for product placement and on design and packaging to produce an aura of quality.

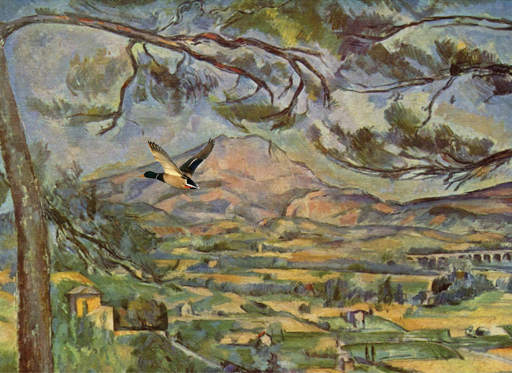

Goose was shipped in wood crates, just like best French wines. He designed an elegant and distinctive bottle with smoked glass and a silhouette of flying geese, taken from a painting by Cezanne whose paintings were selling for astronomical sums at the world’s elite art auctions.

Bottle was part frosted, part clear so that people could see a perfectly translucent liquid. At the same time it would catch the light and would look fantastic behind the bar.

Influencers, Events and PR

Before Goose even hit the market Frank teamed with one of his chefs, Pascal Courtin, to create a cookbook of recipes containing Grey Goose vodka.

He was giving away cases to any charity event that wanted vodka at its bar knowing that people at charity events are his target audience. He even deposited bottles in limousines used for the Academy Awards ceremony.

The Goose started with a bold price at around $30 a bottle, roughly twice the price of other premium vodkas and he submitted right away two bottles to the Chicago-based Beverage Testing Institute. Few weeks later Grey Goose won as the best-tasting vodka in the world.

That was the sign Frank was waiting for. He found the hottest nights in the hottest clubs of New York, Chicago and Los Angeles and would put bottles in the hands of the hottest people. He influenced the influencers. The trend setters and arbiters who like to tell their friends what to buy. Frank found them and gave them the best product with the most convincing story they ever heard. Frank made sure to give the bars and clubs big, 1.75-liter bottles, to grab attention and to catch the eye. The machine was on and early adopters were hooked.

And the market responded. $3 million profits in 1st year. Frank took it all and put it into advertising. Including a daily ad in the Wall Street Journal. “We made big, beautiful ads that listed Grey Goose as the best-tasting vodka in the world, and indoctrinated the distributors and over 20,000 bartenders. So when somebody would come in and say, what’s your best-tasting vodka, they said Grey Goose.”

Grey Goose’s success was stellar. Frank had called the market correctly once again and a legend was born.

And then.. the imbelivable happened.

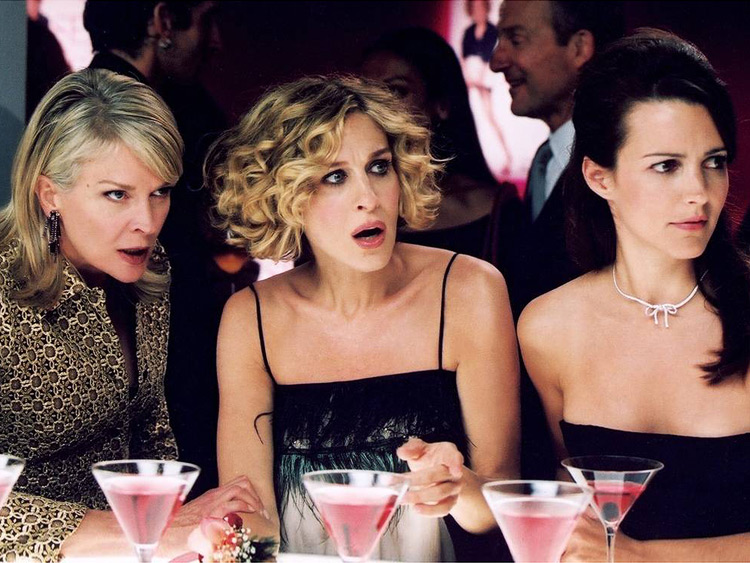

Sex and the City, the acclaimed and crazy popular HBO show that followed the lives of four women in their mid-thirties was not only driving conversations about sex, femininity, friendships and romance it became a major influencer of postmodernist urban culture.

Adapted from a weekly newspaper column written by Candace Bushnell, a New York journalist, it re-mediated a range of taboo content through smart and sophisticated entertainment that viewers were craving for years.

It’s impact was felt in language, fashion and even politics. Sex in the City introduced expressions such as: “He’s just not that into you”, “Abso-fucking-lutely” and “Frenemy”. It’s style-driven weekly episodes turned luxury brands into household names, from Magnolia Bakery cupcakes and Fendi handbags to Manolo Blahnik shoes and of course Grey Goose Cosmopolitans.

When Sarah Jessica Parker started stirring “Goose Cosmos” the battle for vodka supremacy was over. Grey Goose had won.

In 2004 Goose sold 1.5 million cases or 18 million bottles and Bacardi made an offer of over $2 billion.

Sidney Frank took it.

The brilliance of his success lied in how easy he made it look. Unlike his competitors who played by rules and frameworks of categories they were in, Frank aspired to be something different from the start: A category of one.

He gave huge bonuses to his employees including a $23.4 million to his secretary

that’s been following him since 1970’ and $120 million to Brown University which he had to leave in 1943 as a freshman when his money ran out.

He hired a group of full-time golf pros at a cost of perhaps half a million dollars a year, and made them play the game on his schedule. He became famous for random acts of generosity to people he liked, giving away $500 tips to waiters, drivers and homeless people on streets of New York. He funded the Israel Olympic Committee, a new Science Center dedicated to Alan Turing and multiple travel magasines. He has spent the last two years of his life promoting a new tequila brand called Corazon and an energy drink Crunk, with rapper Lil’ John.

He died on January 10, 2006 on a private plane in flight between San Diego and Vancouver at the age of 86 from heart failure.

In the last decade, a string of mergers and acquisitions reshaped the fragmented global liquor industry, leaving it dominated by a few international powerhouses such as Diageo (Smirnoff, Johnnie Walker, Baileys, Guinness, Moët & Chandon, Hennessy), Pernod-Ricard (Absolut, Chivas Regal, Havana Club, Jacob’s Creek, Jameson, Ricard, Beefeater) and Domecq (Courvoisier, Canadian Club, Kahlúa, Malibu, Tia Maria etc.).

Shortly after, shareholder’s pressure forced liquor companies to work through distributors rather than dealing directly with retail outlets marketing was mostly spent on nationwide ad campaigns.

But today, after years of failed product launches, most spirits giants started imitating Frank tactics to ensure that brands get better treatment with retailers and restaurants: giveaways, continuous courting of bartenders, influencing of influencers and experiential event marketing.